Commander George Washington Rodgers and the Action of August 17th, 1863

Photo: Commander George Washington Rodgers, USN (Naval History and Heritage Command Photo)

On August 17th, 1863, the ironclads of the Rear Admiral John Dahlgren's South Atlantic Blockading Squadron advanced against Battery Wagner on Morris Island, South Carolina. The plan was to use the monitors' heavy guns - six 15-Inch Dahlgrens, four 11-Inch Dahlgrens, and two 150-Pounder Parrott rifles between them - along with New Ironsides's imposing broadside battery to disable to fort. US Navy wooden gunboats would also contribute to the bombardment at long range.

USS Catskill, under the command of Commander George Washington Rodgers, would push closest to the shore. According to the Confederate report of the action, Castkill closed within 500 yards - so close that the 10-Inch Columbiad ashore could not depress enough to fire upon the monitor's turret. Firing at maximum depression, the Columbiad would instead strike the top of Catskill's pilot house.

After the action, Catskill's Executive Officer, Lieutenant Commander Charles Carpenter would write:

"About 8:30 a shot struck the top of the pilot house, fracturing the outer plate, and tearing off an irregular piece of the inside plate of about one square foot in area, and forcing out several of the bolts by which the two thicknesses are held together, pieces of which struck Captain George W. Rodgers and Acting Assist ant Paymaster J. G. Woodbury, killing them instantly, also wounding the pilot, Mr. Penton, and Acting Master's Mate Truscott, after which I hove up the anchor, steamed down to the tug Dandelion, transferred them to her and returned, taking position astern of the Weehawken, continued the fire until signal was made to withdraw.

We were struck in all thirteen times." (Official Records - Navies. Ser. 1. Vol. 14. Pg. 498.)

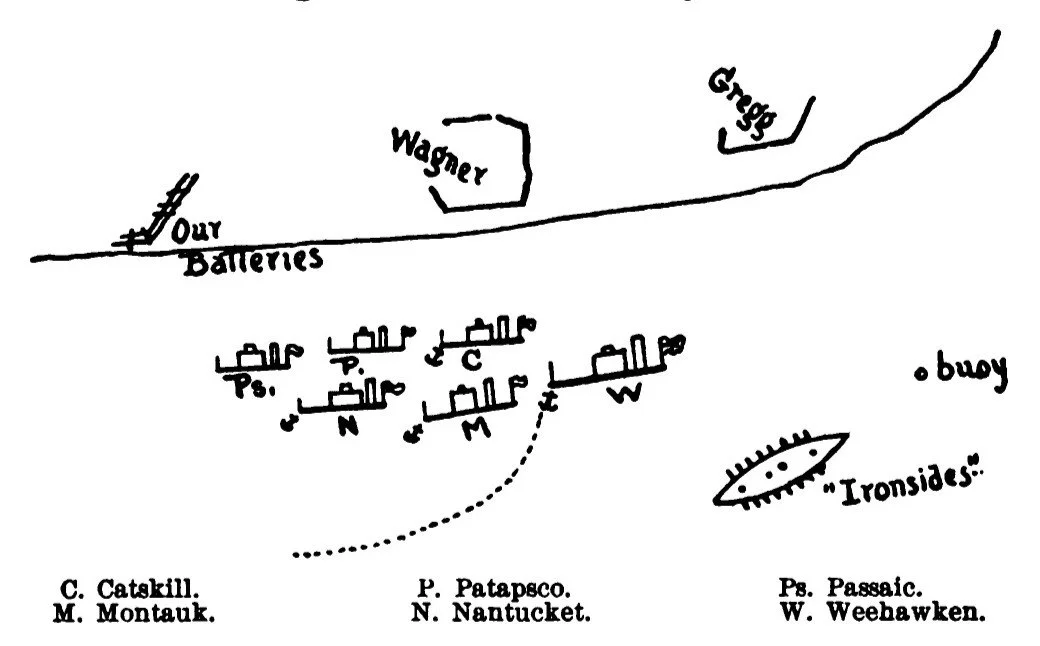

Admiral Dahlgren's illustration of the Action of August 17th. See Official Records - Navies. Ser. 1. Vol. 14. Pg. 454.

Dahlgren would deeply mourn the loss of Rodgers writing in his report to Gideon Welles:

The officers and men of the vessels engaged have done their duty well, and will continue to do so. All went well with us save one sad exception-Captain Rodgers, my chief of staff, was killed, as well as Paymaster Woodbury, who was standing near him. Captain Rodgers had more than once asked me on this occasion if he should go with me as usual, or resume command of his vessel, the Catskill, and he repeated the query twice in the morning, the last time on the deck of the Weehawken, just while preparing to move into action. In each instance I replied, "Do as you choose." He finally said, "Well, Iwill go in the Catskill, and the next time with you."

The Weehawken was lying about 1,000 yards from Wagner, and the Catskill, with my gallant friend, just inside of me, the fire of the fortcoming in steadily. Observing the tide to have risen a little, I directed the Weehawken to be carried in closer, and the anchor was hardly weighed when I noticed that the Catskill was also underway, which I remarked to Captain Colhoun. It occurred to me that Captain Rodgers directed the movement of the Weehawken, and was determined to be closer to the enemy, if possible. My attention was called off immediately to a position for the Weehawken, and soon after it was reported that the Catskill was going out of action, with signal flying that her captain was disabled. He had been killed instantly.

It is but natural that I should feel deeply the loss thus sustained, for the close and confidential relation which the duties of fleet captain necessarily occasion impressed me deeply with the worth of Captain Rodgers. Brave, intelligent, and highly capable, devoted to his duty and to the flag under which he passed his life. The country can not afford to lose such men. Of a kind and generous nature, he was always prompt to give relief when he could. I have directed that all respect be paid to his remains, and the country will not, I am sure, omit honor to the memory of one who has not spared his life in her hour of trial.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

JNO. A. DAHLGREN,

Rear-Admiral, Comdg. South Atlantic Blockading Squadron"

(Official Records - Navies. Ser. 1. Vol. 14. pp. 453-454.)

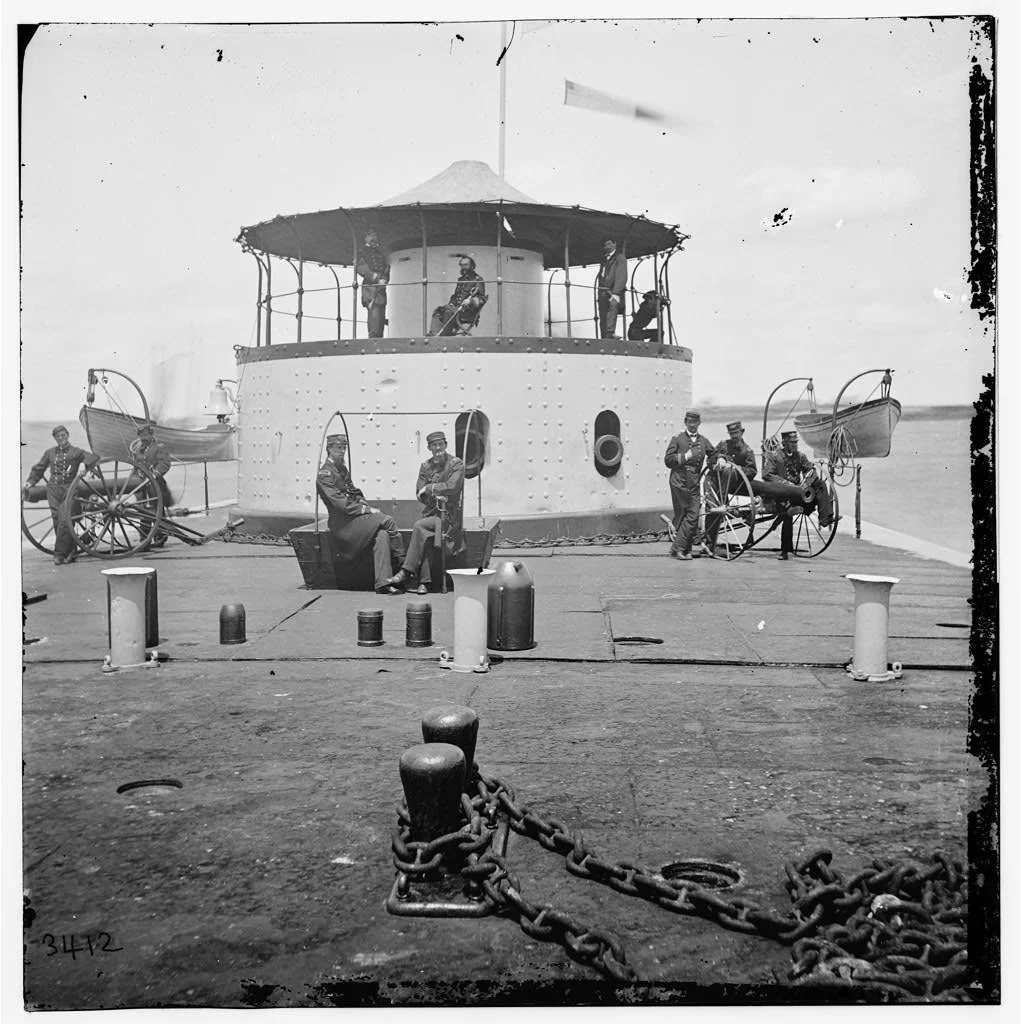

Turret of USS Catskill at Charleston in 1865. Note the 15-Inch Dahlgren which cannot be run out of the gunport and the 11-Inch which can be. Note the two boat howitzers - at least on of which is rifled. Also note the (presumably taken from forts ashore) Confederate projectiles on the deck. I assume the smaller ones are 6.4-inch or 7-inch bolts. Is the enormous one for the 12.75-inch Blakely? (Library of Congress Photo: https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666835/)

Battery Wagner was damaged, though not severely. One of the two sea face 10-Inch Columbiads was disabled when a 15-Inch shell burst near the gun - destroying the chassis (lower portion) of its carriage but not harming the cannon itself. Through the action, the two Columbiads had each fired about once every ten minutes. The other sea face gun, a rifled and banded 32-Pounder, would be struck and destroyed by a 15-Inch shell fired from a monitor the following day. (See Official Records. Navies. Ser. 1. Vol. 14. pp. 484-486.)

However, it was the US batteries on land which made the greatest impact on the Confederate fortifications. Eleven heavy rifles - up to 200-Pounder Parrotts (US Army term for the 8-Inch) - began their work to destroy Fort Sumter at long range. For example, a 200-Pounder, firing at more than 3,000 yards, struck the brick of Fort Sumter leaving a three foot diameter crater - the projectile only stopping after pushing through five feet of solid brick.

Then Lieutenant John Johnson, CSA, wrote (in 1889) "The total firing between 5 A. M. of the 17th and 5 A. M. of the 18th of August was 948 shots, of which 445 struck inside, 233 struck outside, and 270 passed over the fort. After this first day's battering fire from those eleven rifled guns it became a settled conclusion that the ruin of the brick Fort Sumter was an assured thing, a matter of time alone. Henceforth it became the duty of the defense to delay the demolition as long as possible, and to save all material of war that could be spared” (Johnson, pg. 117-121).

10-Inch Confederate Columbiad displayed on a reproduction carriage at Fort Moultrie. See more photos of this cannon here: https://www.santee1821.net/preserved-artillery/10-inch-confederate-columbiads-at-fort-moultrie