USS Franklin (1867-1915), Flagship of Admiral Farragut

This post is available as a video on YouTube and is linked above.

In the early 1850s the old ship of the line USS Franklin had been out of commission for more than twenty-five years. Built at the end of the War of 1812, Franklin first commissioned in 1817 - and saw service as the flagship of the Mediterranean and Pacific squadrons before decommissioning in 1824.

Like the other first-generation US Navy ships of the line, USS Independence and USS Washington, Franklin was simply not quite large enough to carry the heavy gun battery that the Navy fitted her with. Fully loaded, her lower deck gun ports were only about four feet above the waterline - too little to open in any kind of weather.

Painting above: “The U. S. Ship Franklin, with a View of the Bay of New York” via Wikimedia

By the mid-1820s a larger second generation of American ships of the line entered service. Franklin was no longer needed for active service.

In 1852, USS Franklin was towed from Boston to Portsmouth Navy Yard in Kittery, Maine to test the new floating dry dock there. The next year it was proposed to razee the old ship - removing her top deck and turning her into a heavy frigate. The plan for this proposal still exists in the National Archives.

Her sister, USS Independence, had been razeed in the 1830s. Removing the weight of the spar deck and reducing the battery had transformed a ship-of-the-line of dubious utility into a powerful frigate. It is unclear whether or not any conversion work was done before in 1853 a committee of Naval Officers and Engineers recommended substituting a steam frigate for the old Ship of the Line.

Illustration above: 1852 Proposal to Razee USS Franklin. US National Archives

Throughout the 19th Century, the US Navy repurposed its repair budget to build entirely new ships. Wooden ships had to be repaired on a regular basis - wood rots. While in many cases these repairs were actual repairs - see Constitution under repair in the 1850s, occasionally a ship was either too far gone for economical repair, or it was simply an obsolete design that the navy didn’t need anymore. Such was the case with the famous old USS Constellation, which in the early 1850s had rotted to the point of sinking. The Navy kept her name on the books, reported that she was to be repaired, but in fact built an entirely new ship - maybe taking a few symbolic timbers from the old ship over, but little else. Officially, she was the old ship and was celebrated as such. People tend to believe what they want to believe, and it was not until the 1990s that the organization overseeing Constellation in Baltimore accepted that she was, in fact, newly built in the 1850s.

Photo: USS Constellation at Baltimore (see more photos here)

USS Franklin appears to have been a slightly different situation. While the steam frigate was connected to the earlier ship of the line throughout her career, the navy seems to have been a bit more forthright that this was a new ship. The Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for 1853 describes the work in terms of conversion, stating, “The old ship-of-the-line, the Franklin, is being repaired at Kittery, and her model much changed, with a view of converting her into a first-class steam-frigate.” However, by the 1855 Report, Franklin is listed alongside Niagara, Wabash, Roanoke, Colorado, and Minnesota as new construction.

It may be that the Navy couldn’t quite keep a lid on the fact that the new ship was so much larger than the old. Even the most lubberly member of Congress might take note of a ship that somehow emerged from a repair nearly 80 feet longer and three feet wider than she had entered it.

The research of Donald Canney has also shown that the plan for the “rebuilt” Franklin was the model for the Merrimack class frigates - Roanoke and Colorado, in particular, closely matching Franklin. However, the Merrimacks would all enter service well before Franklin. USS Merrimack commissioned in 1856 and her sisters would follow, all seeing service prior to the American Civil War.

Franklin, however, remained on the stocks, slowly building. Whether this is due to her being rebuilt with repair funds or simply not being a priority, I do not know. With the coming of Civil War, the need was far shallow draft ships, and after Wabash captured forts at Cape Hatteras and Port Royal and Minnesota escaped destruction by the guns of her erstwhile sister, there was little need for the big frigates which couldn’t enter most southern harbors. They served in support roles - and it was not until 1863 that machinery was ordered for her - and she would not be launched until September of 1864.

Franklin benefited from having machinery almost a decade more advanced than the Merrimacks. She made over 10 knots under steam - considerably better than the other American steam frigates had done.

Photo: USS Franklin launching at Porstmouth Naval Shipyard (Kittery, Maine) in September of 1864. Notice the civilians watching the launch at left. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/80-CF-02000/80-CF-2393-1.html

Though her half sisters had been armed to the teeth during the Civil War, with Colorado eventually carrying 46 9-Inch Dahlgrens with a 150-Pounder Parrott and 11-Inch Dahlgren as pivots on either end of the spar deck, there was no need for Franklin to carry such a heavy battery in peacetime. She mounted thirty-four 9-Inch Dahlgrens, four 100-Pounder Parrotts, and a single 11-Inch Dahlgren - likely in the forward pivot position on the spar deck.

Having missed the entirety of the Civil War, USS Franklin was fitted out in 1867 to be the flagship of the Mediterranean squadron. David Farragut, hero of the US Navy during the American Civil War for his victories at New Orleans and Mobile Bay, was newly promoted - the US Navy’s first full admiral.

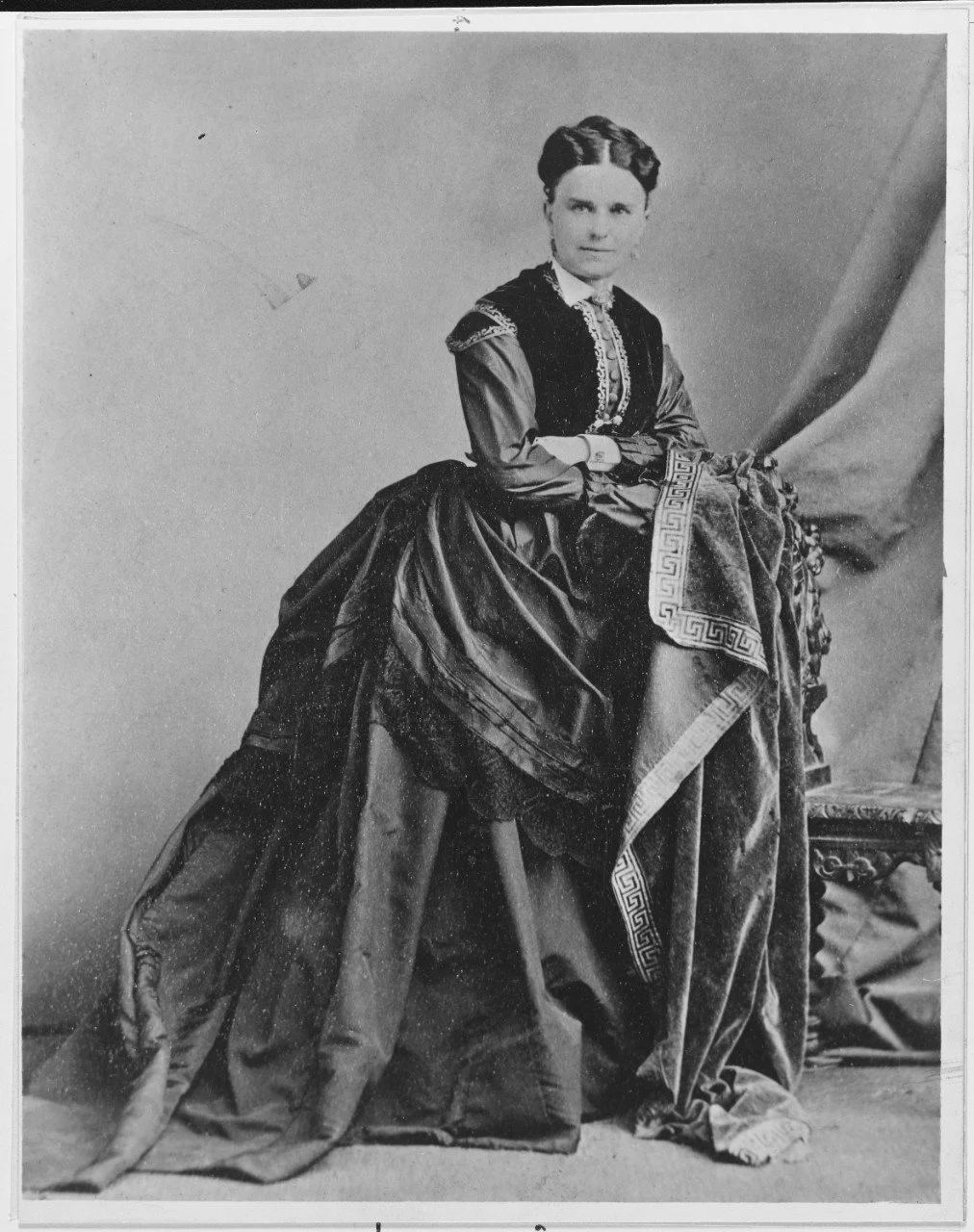

President Johnson sent a telegram to Admiral Farragut giving permission for Mrs. Farragut to accompany the Admiral on the voyage. Permission was also extended to the wife of Captain Penncock as well. This was not merely to give Admiral Farragut and Captain Penncock the companionship of their wives on the year-long voyage. The mission ahead of them was largely diplomatic. Over the coming year, the two officers would be attending innumerable functions ashore in every port of call and hosting nearly as many on board. The women would in a very real sense assist the diplomatic efforts of the United States.

Photos:

Admiral Farragut aboard USS Franklin: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-49000/NH-49527.html

Virginia Loyall Farragut: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-49000/NH-49528.html

On June 17th, 1867, President Johnson came on board USS Franklin, then at New York. All of the ships present - and visiting French warships - rendered the president a 21 gun salute. On June 28th, USS Franklin set sail for Europe. And she did indeed set sail, as she experimented with whether it was more efficient to go to the trouble of hoisting the propeller or just letting it spin. It was found that she was two to three knots faster with the propeller hoisted. Franklin arrived at Cherbourg on July 14th. On July 27th, Admiral Farragut was in Paris dining with Emperor Napoleon III - where he discussed the ironclad Dunderburg, which had been built in the United States but had been purchased by France as the US Navy no longer needed her.

USS Franklin then headed for the Baltic where she hosted Admirals and Royals in Prussia, Russia, and Sweden before arriving in the United Kingdom. Farragut was shown the results of testing a US Navy 15-Inch Dahlgren and a British 9-Inch Muzzle Loading Rifle against armored targets. Farragut wrote that the tests revealed that the 9-Inch Rifle penetrated the targets better though the American 15-Inch had more crushing power - Farragut concluding that the American smoothbore was the better weapon against armor, though British accounts of the tests conclude quite the opposite.

Painting depicting USS Franklin displayed at the United States Naval Academy. Photo by Gerald Todd.

On October 22nd, Farragut went on board HMS Agincourt, then fitting out. The contrast between USS Franklin, a wooden steam frigate of the 1850s armed with cast iron smoothbore shell guns and Agincourt, a massive iron-hulled armored ship with the latest built-up rifled guns, was immense. When USS Merrimack had first arrived in European waters in 1856, she was one of the most powerful ships in the world. Ten years later, her near sister could barely hope to scratch the paint of an ironclad like Agincourt. For all of the hospitality shown to the famed Admiral Farragut naval officers in Britain and on the continent, there was no getting around the fact that the flagship of the American squadron was hopelessly obsolete as a ship of war.

USS Franklin next visited the Mediterranean. At Malta on Easter Sunday in April 1868, as USS Franklin entered Valletta harbor, USS Franklin was greeted with the band aboard the British flagship HMS Caledonia playing the Star Spangled Banner - which Franklin’s band returned playing “God Save the Queen.” At Malta, Farragut and Franklin’s officers were the honored guests at a number of balls and receptions. Franklin, in turn, hosted her own ball aboard. The ship was festooned with flags, and there was waltzing on the gun deck as the British officers and their wives were welcomed aboard the American flagship.

Franklin returned to the United Kingdom. Receiving word that the Prince of Wales wished to visit the ship, Franklin’s crew made ready and on July 14th, 1868 the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert came alongside and the future King Edward VII and his brother Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh came aboard. On July 16th, Admiral Farragut was welcomed aboard HMS Galatea - which was commanded by the Duke of Edinburgh, a Royal Navy Captain, who, with his crew, had just returned from a round-the-world voyage.

Franklin visited Italy before returning to New York in November of 1868.

USS Franklin would continue in active service through 1876. Her last duty was to transport William “Boss” Tweed, who had been arrested in Spain, back to the United States.

Photo: USS Franklin in the early days of her career as a receiving ship. While she retained her rig at first, she was eventually housed over. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-53000/NH-53945.html

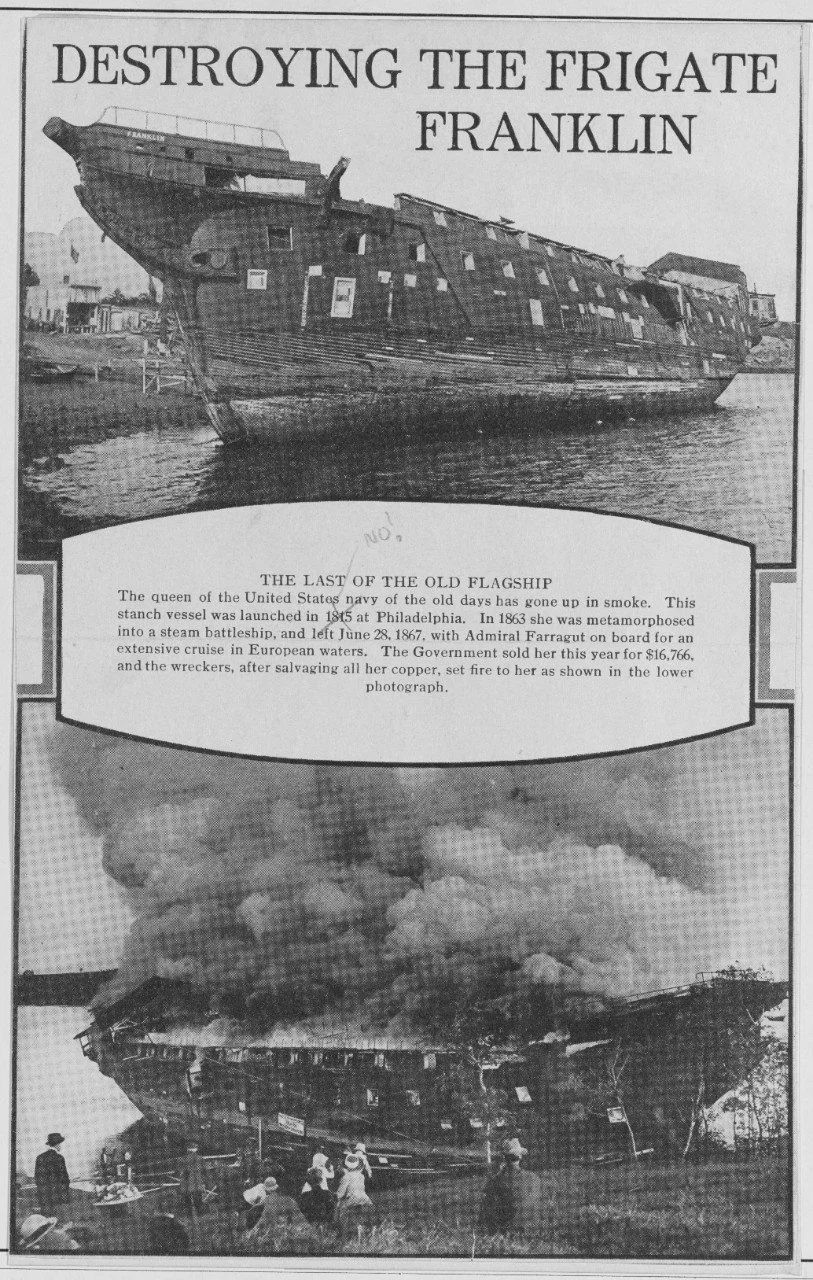

From 1876, USS Franklin served as a receiving ship at Norfolk. She helped train generations of American sailors. Eventually she was housed over - and for years she was docked near USS Richmond. In 1915 she was sold and like so many other famous and long serving ships of the US Navy, she was burned to recover her metal fittings. She came to her end near Eastport, Maine.

One of her 100-Pounder Parrott Rifles survives at Norfolk Naval Shipyard. 100-Pounder Parrott Number 165 served aboard USS Franklin - likely from the time of her commissioning until at least 1872, though the Parrott’s presence at the shipyard makes me wonder if it wasn’t aboard when the steam frigate arrived in 1876.

USS Franklin was a fine ship, and a fitting flagship for the United States Navy’s first full Admiral, David Farragut. She and her crew helped the United States build its relationship with European powers in the years immediately following the Civil War - and her career is an example of the importance of the US Navy to the diplomacy of the United States in the 19th Century.

Photos above: The destruction of USS Franklin via NHHC: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-54000/NH-54195.html

US Navy 100-Pounder Parrott Rifle Number 165: See more photos of this Parrott here.

Sources used for this post include:

Canney, Donald L. The Old Steam Navy: Frigates, Sloops, and Gunboats, 1815-1885. Naval Institute Press, 1990.

Canney, Donald L. Sailing Warships of the US Navy. Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Chapelle, Howard I. The History of the American Sailing Navy: Their Ships and Their Development. W.W. Norton, 1949.

Farragut, Loyall. The Life of David Glasgow Farragut, First Admiral of the United States Navy, Embodying His Journal and Letters. New York, 1891. Available here: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008376021

Olmstead, Edwin, Stark, Wayne E., Tucker, Spencer C. The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast, and Naval Cannon. Museum Restoration Service, 1997.

Reference was also made to the Logbooks of USS Franklin on the National Archives Website.