The 100-Pounder Parrott Rifle of USS Dawn at York, Maine

US Navy 100-Pounder Parrott Rifle Number 206 at York, Maine

Many thanks to John Weaver for taking a detour to photograph Number 206 and share the photos. John is the author of A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coast Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867. Available here.

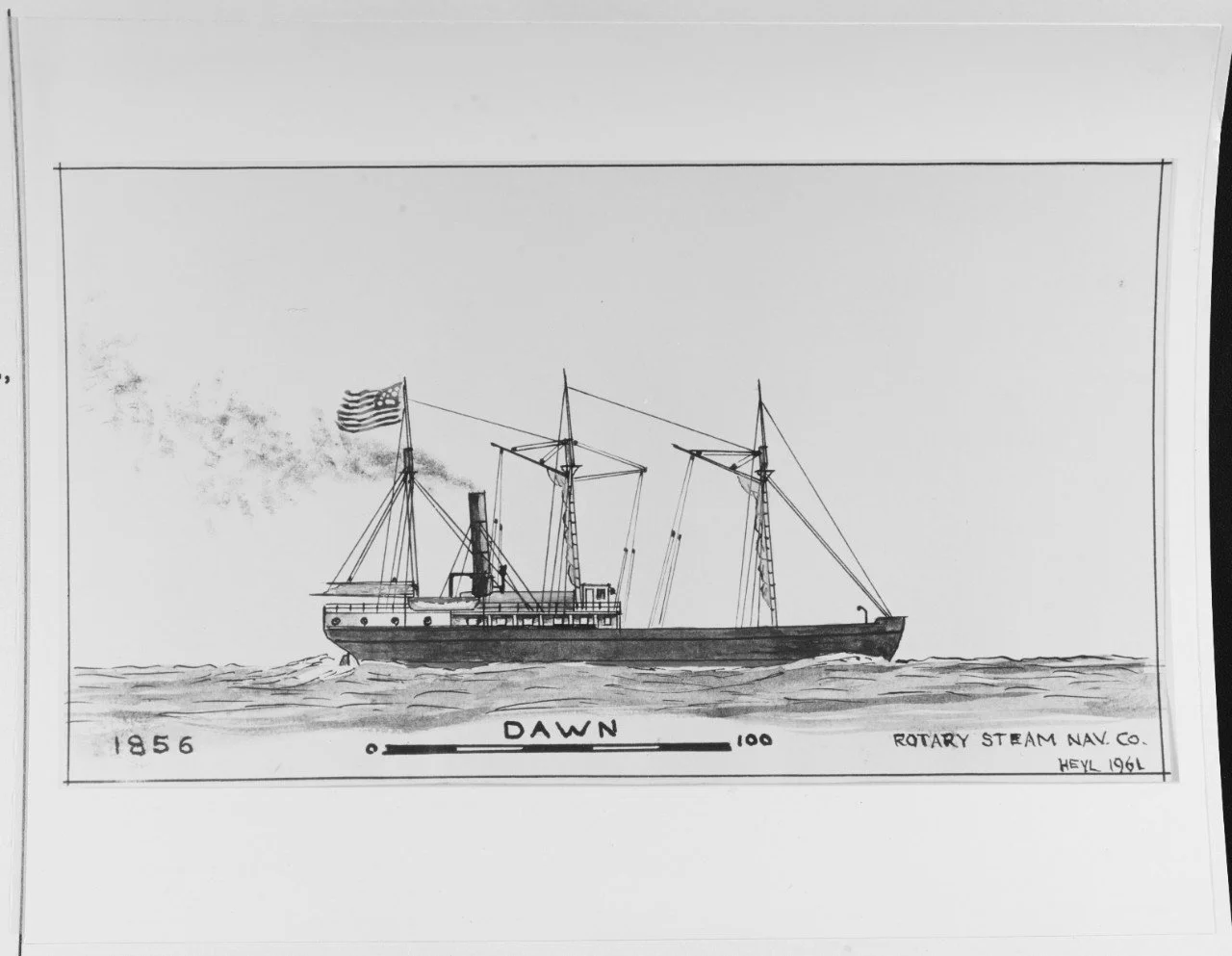

A US Navy 100-Pounder Parrott Rifle, US Navy Registry Number 206, is displayed in front of the Old Gaol in York, Maine. Number 206 was cast at West Point Foundry in 1863. It’s weight as manufactured is 9,672 pounds. According to the research of Olmstead, Stark, and Tucker, Number 206 served aboard USS Dawn during the American Civil War (pg. 218). USS Dawn was a merchant steamer built in 1856/1857. It was taken into US Navy service in 1861. Initially armed with a main battery of two 32-Pounders of 57 Hundredweight and a 20-Pounder Parrott, the 32-Pounders were replaced with a single 100-Pounder Parrott in 1863 - likely the same Parrott now in York. Also according to Olmstead et al., USS Dawn’s 20-Pounder may be seen at Berwick, Maine.

USS Dawn and the Battle of Wilson’s Wharf

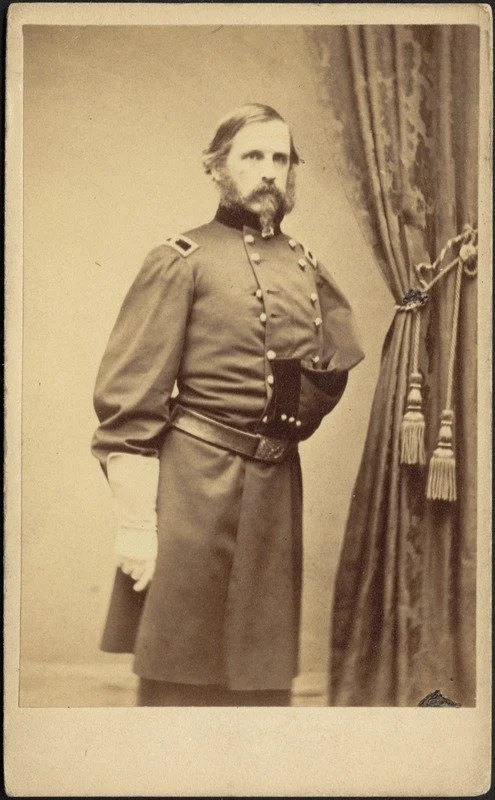

On May 24th, 1864, elements of three Confederate Cavalry brigades under the command of Major General Fitzhugh Lee attacked Fort Pocahontas at Wilson’s Wharf on the James River which was defended by the 1st United States Colored Troops and elements of the 10th USCT under Brigadier General Edward Wild, a homeopathic physician from Massachusetts who had served in the Ottoman Army during the Crimean War, volunteered as an infantry officer at the start of the Civil War, and had lost an arm at the Battle of South Mountain. Wild assisted Colonel Shaw in finding officers for the 54th Massachusetts, and he had gone on to raise a brigade of African American troops. His operations made him notorious in the eyes of the Confederates, particularly because of his December 1863 raid into North Carolina where he and his troops liberated over two-thousand enslaved persons (Casstevens, Frances H. Edward A. Wild and the African Brigade in the Civil War, pg. 115).

Edward Wild - Photo from the Boston Public Library

The very presence of USCT soldiers and General Wild at Wilson’s Wharf goaded Confederate President Davis to act. According to Gordon C. Rhea, “There was no military reason to send Lee to Wilson’s Wharf. The enclave of black troops posed no immediate threat to Richmond, and the Army of Northern Virginia sorely needed its cavalry to fight Grant. Political considerations, however, prevailed over military ones” (Rhea, Gordon C. To the North Anna River, pg. 363).

After riding all night from Richmond, Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry arrived at Wilson’s Wharf in the early morning of May, 24th. The cavalry dismounted and attacked the fort. Though his initial attack was unsuccessful, Fitzhugh Lee sent under a flag of truce a demand to the defenders of the fort surrender. The demand came with the promise that if the defenders promptly surrendered, they would be treated as prisoners of war. If they continued to resist, Fitzhugh Lee stated he could not be responsible for the consequences. The implied threat was a repeat of the Fort Pillow massacre. If Wild didn’t surrender his men immediately, all would be killed or taken into slavery (Casstevens, pg. 173).

Wild took a used envelope from his picket and wrote a terse note as his reply to General Lee: “We will try that.” (Simonton, Edward. “The Campaign Up the James River to Petersburg”. pg. 484).

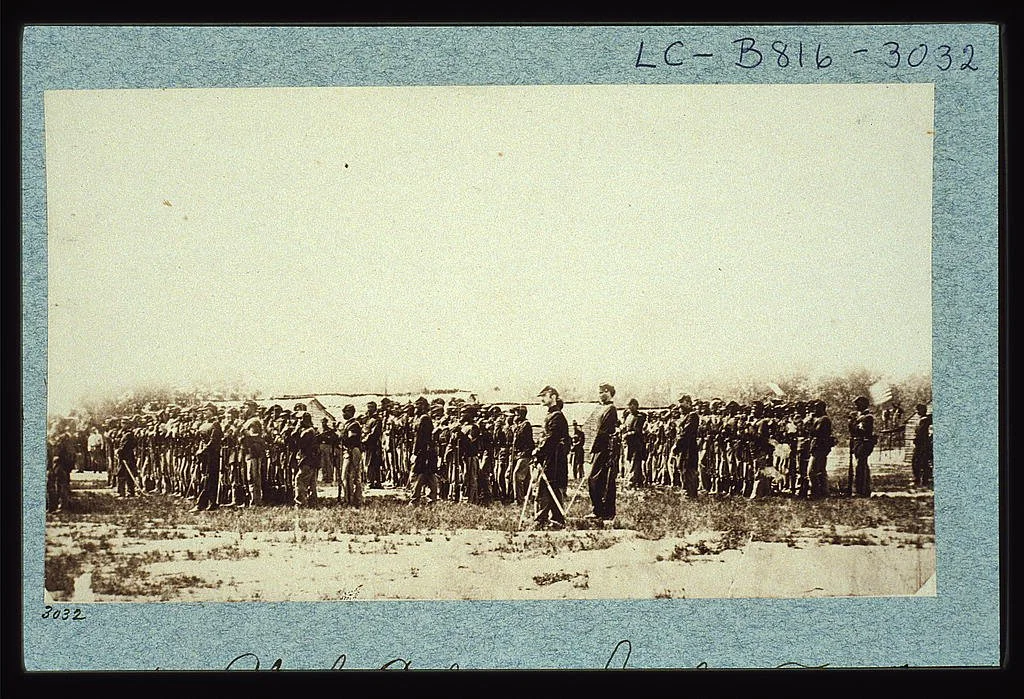

Captain Edward Simonton, one of the 1st USCI’s officers wrote of the battle, “On the receipt of Gen. Wild's answer to his demand for surrender, the enemy began the attack on our position. Dismounting their men, they first made a feint attack on the left and center of our line and then made a direct charge on our right. The surrounding woods favored the enemy so that they were able to advance quite near our works before the fire from our line could have much effect on them. But as some of the "Johnnies" showed themselves to our view, they received a destructive fire from our line. Still the enemy charged on with a yell, firing all the time as they advanced, and seemed confident of their ability to drive all our force into the river. Then it was that our sable warriors showed their fighting qualities. They stood their ground firmly, firing volley after volley into the ranks of the advancing foe. Many of the "Johnnies" had succeeded in approaching quite near our line. The artillery stationed in our works then threw grape and cannister into their ranks. Again the brave and determined foe rallied under the frantic efforts of their officers; again their ranks were scattered and torn by our deadly fire. Next the gunboat in the river began to throw shells into their already demoralized ranks, when they broke and fled in disorder to the rear; then our soldiers poured into their ranks a final volley, and this was the last of the fight. They left on the field a portion of their dead and wounded. It was reported that the enemy's loss was over 100 dead and wounded. We took several prisoners, including one Major. Our total loss was two killed and 14 wounded, including one officer” (Simonton, pg. 485-486).

General Wild would write, “The gunboat Dawn (Captain Simmons, Executive Officer Jackaway) rendered most efficient and material aid in shelling the enemy on both flanks, changing her position according to need. They have received my heartfelt thanks.” (Official Records. Ser. 1. Vol. 36. Pt. 2. Pg. 271).

Rhea quotes soldiers describing the big 100-Pounder shells as looking like “turkey gobblers flying over” or “as great black masses, as big as nail kegs, hurtling in the air and making the earth tremble under us and the atmosphere jar and quake around us when they burst” (Rhea, pg. 365). The Confederate troopers retired under heavy fire, having taken some 200 casualties. Their attack defeated, they withdrew from the area.

1st United States Colored Troops in formation for review. Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/2004673345/

The commander of USS Dawn reported:

Report of Acting Volunteer Lieutenant Simmons, U. S. Navy, commanding U. S. S. Dawn.

U.S. S. DAWN,

Off Wilson's Wharf, May 25, 1864.

SIR: I have the honor to report that at 1:30 p. m. yesterday, the 24th, the United States forces under General Wild, at this point, were very suddenly attacked by the enemy in heavy force under General Fitzhugh Lee. On hearing the alarm, I at once got underway and commenced shelling the woods on our left flank.

The enemy got possession of a small piece of woods above the fortification and the transport steamer Mayflower coming by at the time, they opened a galling fire of musketry on the Mayflower and this vessel, badly wounding the captain and pilot of the transport. I at once opened on the woods and succeeded in driving them out.

The firing having almost ceased on our left and increased on our right flank, altered the position of this vessel, and commenced shelling the enemy just as they were making a charge, which drove them back, and, as General Wild tells me, thus ended a sharp action of five and a half hours.

I very respectfully report that if I had two 32-pounders in addition to my present battery, I could do much more service, having now no smoothbore guns to throw grape and canister. The bolts and ports are already on the vessel ready to put the extra guns in position at once, this vessel having carried them on the last cruise in addition to her present battery, and she can carry them now with ease. My ammunition is very nearly out, and I am anxious to get a supply as soon as possible, as I have only 17 rounds remaining, and herewith I send requisition for your approval.

The officers and crew behaved finely, Acting Ensigns William B. Avery, E. T. Sears, and P. W. Morgan serving their different guns with great coolness and energy, although the enemy's sharpshooters were throwing musket shot over and at us continually. I take great pleasure in reporting to you the noble and gallant conduct of my executive officer, Acting Master J. A. Jackaway, in shifting my position to follow the enemy. This vessel got very near a shoal in the river and was compelled to turn by backing for the purpose of getting my guns to bear on the sharpshooters, who were completely showering us with musketry. Mr. Jackaway did the duties of pilot, thus getting the vessel in position, and eventually driving the enemy away and saving that flank of our troops. I do think he deserves promotion if noble and gallant conduct and strict attention to duty merit such a reward.

I am happy to report no casualties on board. I annex a report of ammunition expended during the action.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. W. SIMMONS,

Acting Volunteer Lieutenant, Commanding Dawn.

Report of ammunition expended.

100-pounder rifle: 46 rounds percussion shell.

20-pounder rifle: 34 rounds percussion shell, 1 10-second shell.

Rifled 12-pounder howitzer: 11 rounds percussion shell, 21 rounds, 5-second shell, 3 rounds canister, 2 rounds grape.

Making in all 118 rounds expended.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. W. SIMMONS,

(Official Records - Navies. Ser. 1. Vol. 10. pp 90-91.)

Fitzhugh Lee had been dispatched by Confederate authorities to destroy this threat of armed African American soldiers so close to Richmond. Instead, it was his command that smashed against the determined resistance of the men of the 1st and 10th United States Colored Infantry who knew that they were fighting for their lives and their freedom. This first encounter between the elite cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia and the United States Colored Troops at the Battle of Wilson’s Wharf had a significance beyond its relatively small size. Although the newspapers in Richmond found excuses for the defeat, the fact that the Confederate troopers had been soundly beaten by outnumbered African American troops underlined the fact that these men were very willing and quite capable of fighting for their freedom and Union victory.

The 1st United States Colored Infantry would go on to serve in the Petersburg Campaign before being sent to take part in the successful capture of Fort Fisher and the campaign to capture Wilmington, North Carolina. They, alongside their brigade, are honored by the sculpture “Boundless” by artist Stephen Hayes at the sight of the Battle of Forks Road in Wilmington, North Carolina. The sculpture, showing a file of African American soldiers, was installed in 2021 and is adjacent to the Cameron Art Museum.

The sailors of USS Dawn fought bravely as well - firing 118 rounds from their three rifled guns during the battle. Dawn’s captain lamented not having any smoothbore cannons aboard - as his ship had been close enough to the action to be effective firing canister at the attacking Confederates. Two of USS Dawn’s three guns seem to survive to present. One of the three 20-Pounder’s in South Berwick, Maine was carried aboard USS Dawn as well as the 100-Pounder in front of the Old Jail in York, Maine.

Dutch Gap, Virginia. Picket station of Colored troops near Dutch Gap Canal - Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/item/2018670817/

The Breech of 100-Pounder Parrott Number 206. “R.P.P” stands for Robert Parker Parrott.

The Breech of 100-Pounder Parrott Number 206 showing the weight of 9,672 pounds.

The right trunnion of 100-Pounder Number 206

A 100-Pounder Parrott Rifle aboard USS Mendota on the James River. USS Dawn’s mounting of Number 206 may have looked like this. Library of Congress photo: https://www.loc.gov/item/91787359/

A 100-Pounder shell recovered at Fort Anderson in North Carolina. This shell weighed 92 pounds when filled. It is similar to the forty-six shells fired by USS Dawn’s 100-Pounder at the Battle of Wilson’s Wharf.

Additional Photos of 100-Pounder Number 206

The Old York Gaol, York, Maine and USN 100-Pounder Number 206. By Kenneth C. Zirkel - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59423780