The Wreck of USS Huron and 9-Inch Dahlgren Number 1178

US Navy 9-Inch Dahlgren Number 1178 at Trophy Park at Norfolk Naval Shipyard

Displayed at Trophy Park at Norfolk Naval Shipyard is US Navy 9-Inch Dahlgren Number 1178. Number 1178 was cast in 1864 at Fort Pitt Foundry. It is one of the last of the type to have been manufactured. (The series of registry numbers ran to 1185.) According to the research of Wayne Stark. Number 1178 was recovered from the wreck of USS Huron.

An Impossible Choice off Nags Head

This post is also available as a YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cx8GXnISCyM and a short here: https://youtube.com/shorts/q09vxXLVQyw?

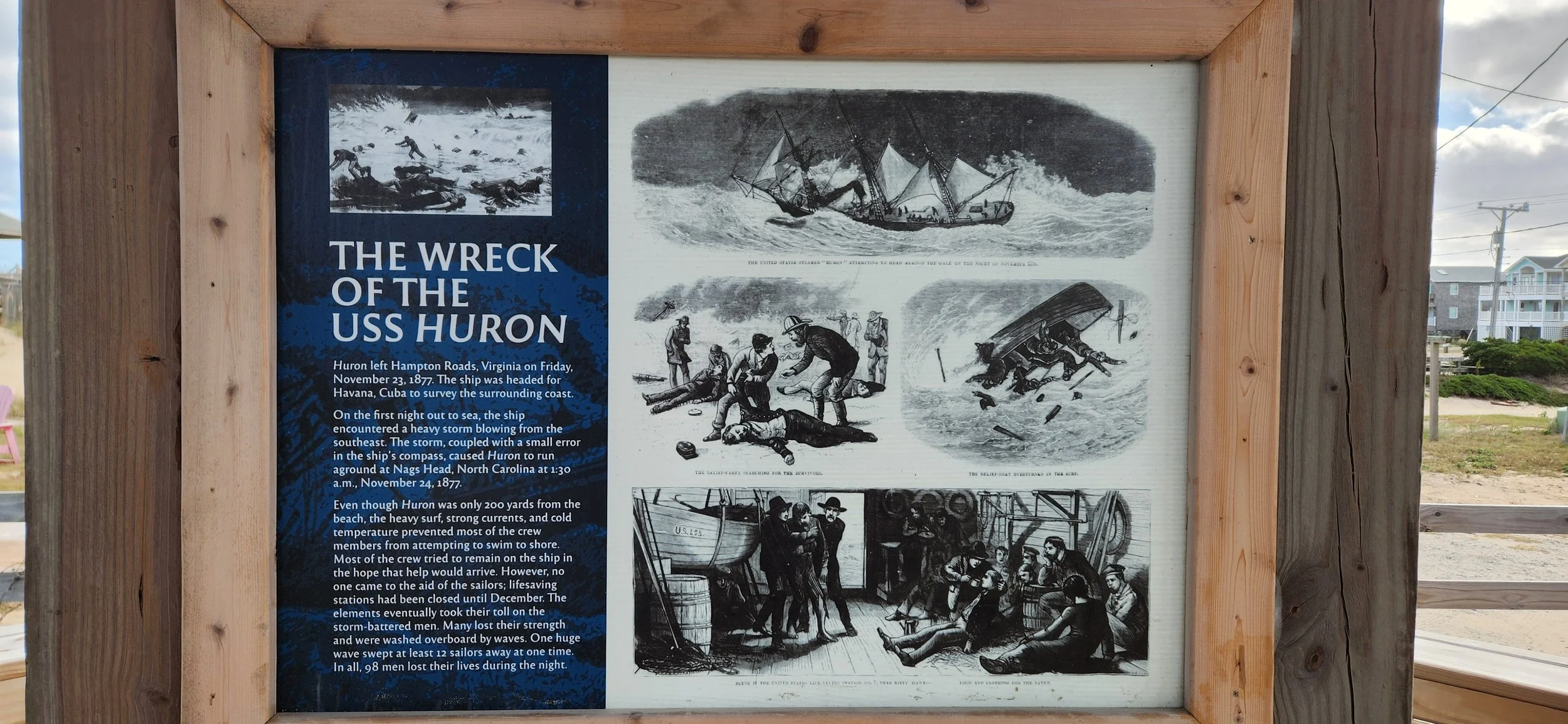

With the wild sea breaking over their stricken vessel, with their boats stove in, and their strength giving out in the cold and spray in the early morning hours of November 24th, 1877, the surviving crew of USS Huron faced an agonizing choice: continue clinging to their ship hoping that rescuers would soon come to their aid or jump into the raging sea and try to swim for the shore an unknown distance away through mist, darkness and crashing waves.

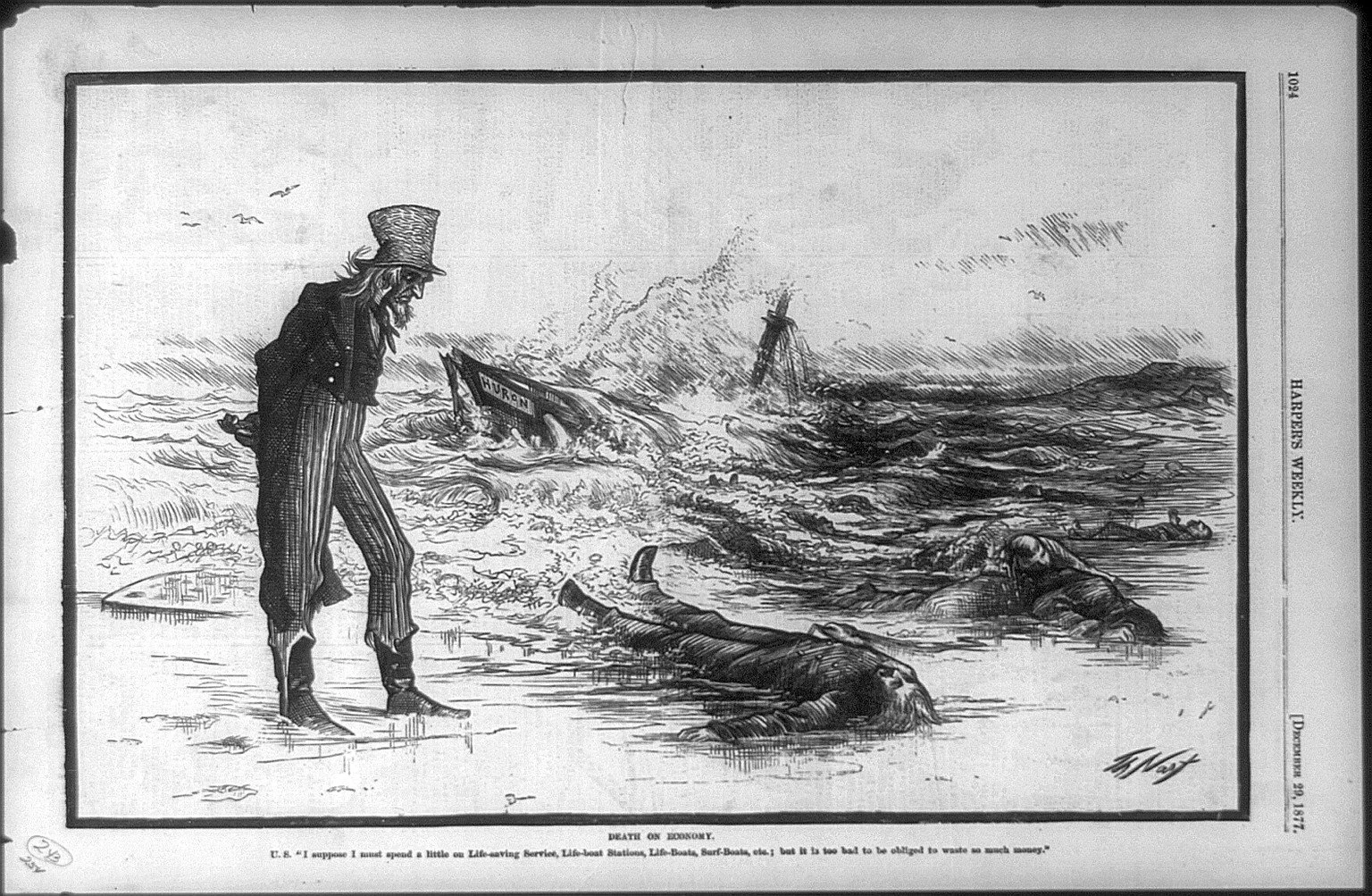

Ninety-eight of Huron’s crew would be lost, many waiting for a rescue that never came. There was a life-saving station just a couple of miles down the beach, but Congress had only provided funding for three months of operation each year. The station would not open until December 1st. Thirty-four men struggled ashore, survivors of a disaster which would help spur the formation of the United States Life-Saving Service as a separate agency in the Department of the Treasury.

USS Huron, an Iron Ship in a Wooden Navy

USS Huron or one of her sisters (USS Alert and USS Ranger) under construction in the 1870s. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-85000/NH-85311.html

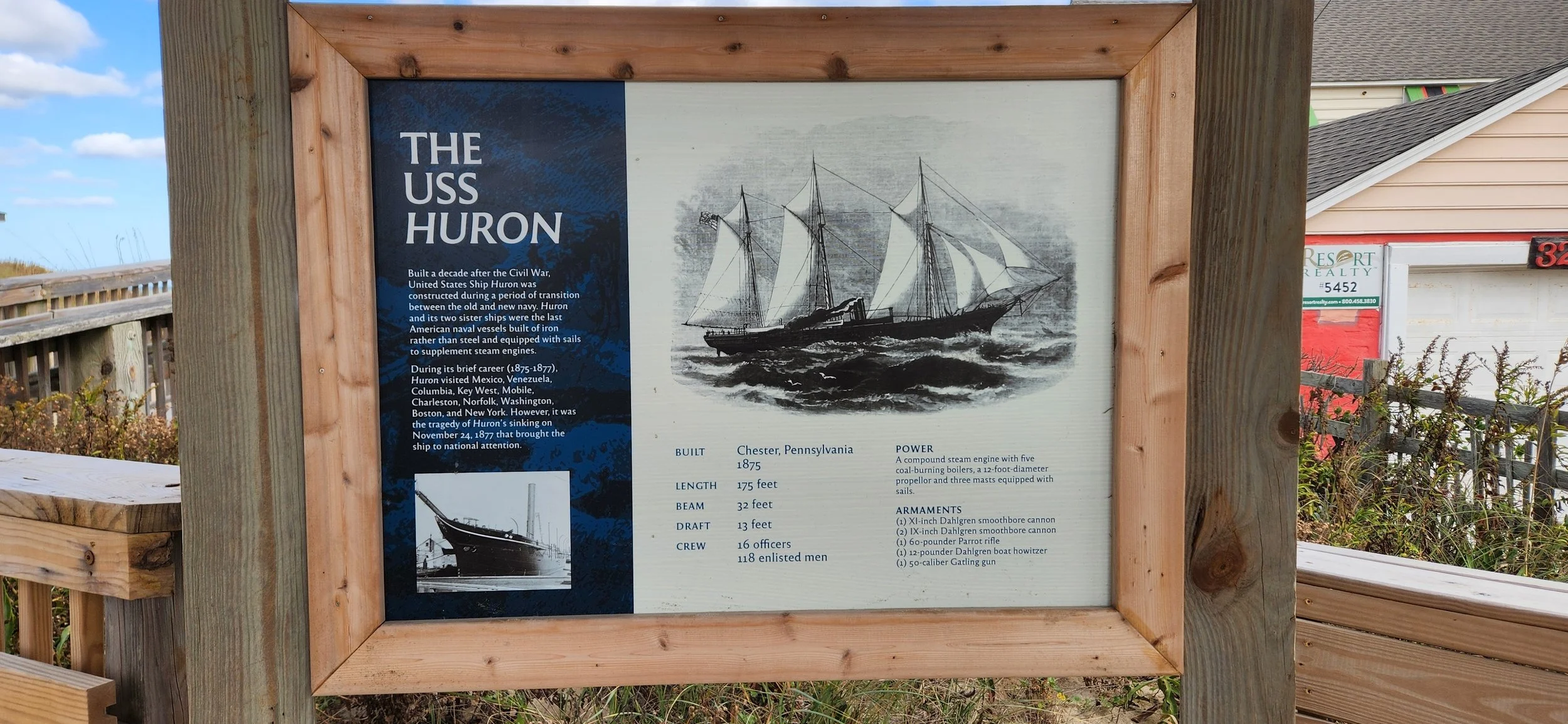

When USS Huron was completed and first commissioned in 1875, she was a rarity - a seagoing iron-hulled ship in a navy that was almost completely wooden. Ten years after the end of the American Civil War, a conflict which saw the first battles between ironclads, almost the entire seagoing fleet of the United States Navy was composed of wooden ships. The iron monitors continued to see some service in harbors and coastal waters, but it was the wooden ships, traveling most of the time under sail or a mixture of sail and steam to minimize the burning expensive coal, which showed the flag in foreign ports around the world.

There was some reason for building with wood. Without armor, iron hulls were just as vulnerable, perhaps more so, than wood to battle damage. Wooden ships could also be given copper sheathing to slow marine growth on their hulls. Iron ships in this period struggled to keep their hulls free of the barnacles and other marine life which would quickly and significantly reduce their speed.

In 1873 Congress authorized the construction of eight new ships. The largest at 3,900 tons displacement was USS Trenton which, though built of wood, was the most advanced cruiser of the US Navy before the steel “New Navy” ships of the mid 1880s. Four were modest nearly 1,400 ton wooden gunboats of the Enterprise class (Enterprise, Adams, Essex, and Alliance - along with Nipsic which was officially a repair of an earlier ship), and three were the even smaller 1,000 ton iron gunboats of the Alert class (Alert, Ranger, and Huron).

The main armament of the gunboats was originally a single 11-Inch Dahlgren smoothbore (most ships would later have this replaced with an 8-Inch Muzzle Loading Rifle). The slightly larger Enterprise class also carried four 9-Inch Dahlgrens while the smaller Alerts carried just two 9-Inch Dahlgrens. Both classes carried a 60-Pounder Rifle. While the Enterprise class and USS Alert were originally fitted as barks, Huron and Ranger were given a schooner rig.

USS Huron and USS Alert were built by John Roach and Sons in Philadelphia. Both commissioned in 1875.

(See The Old Steam Navy: Frigates, Sloops and Gunboats by Donald L. Canney. Pp 154-159.)

USS Huron - Library of Congress Photo: https://www.loc.gov/item/2013646052/

USS Huron, Gunboat of the US Navy

After her commissioning at Philadelphia on November 15th, 1875, USS Huron was assigned to the North Atlantic Squadron at Hampton Roads where in the early spring 1876 her sailors and Marines participated in landing drills with their boat howitzers at Fortress Monroe and drilled alongside the companies of four other ships. In late March, 1876, USS Hartford (flagship of Rear Admiral LeRoy), USS Huron, and USS Marion departed Hampton Roads for Port Royal, South Carolina. In April, Hartford, Marion, Huron, and Shawmut were ordered to the coast of Texas and Mexico to “protect the interests” of American citizens in Mexico.

The Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for 1876 would summerize Huron’s service that year:

The Huron reported at Norfolk December 17, 1875, for duty on the station, and on the 9th of February, 1876, was ordered to Hampton Roads. March 21, left for Port Royal, S. C., arriving there on the 27th. On the 10th of April sailed for Vera Cruz, where she arrived on the24th. Left there, and arrived at Key West on the 10th of June for coal and provisions, and returned to Vera Cruz, reaching there on the 28th. July 1, left Vera Cruz and visited Frontera, Tobasco, Santa Anna, and other ports, returning on the 21st. August 4, arrived at Port Royal, and sailed on the 13th for Portsmouth, N. H.; arrived on the 18th, and left on the 26th for Boston; reached there on the 28th, and sailed on the 16th September for Hampton Roads, where she remains (pg. 330).

In March of 1877, Huron departed Hampton Roads for a cruise along the northern coast of South America. A chief goal of her cruise was to conduct oceanography research.

The United States Steamer Huron, Commander Ryan, has determined the following geographical positions on the north coast of South America and the outlying islands of Unare Bay: Testigos Islands; Puerto Santo Bay; Pampatar, island of Margarita; Cumana; Tortuga Island; Corsarios Bay; Orchila Island; Los Roques Islands; La Guayra; Puerto Cabello; Island of Curaçoa; Vela de Cora; Orange-Stadt; Estanquez Point; Bahia Honda; Cape La Vela; Santa Marta, and Cartagena; carrying the longitudes, chronometrically, between Port Spain, Island of Trinidad, and Aspinwall… a survey was made of the harbor of Orange Stadt by the officers of the United States Steamer Huron. This work was carefully executed, and reflects much credit upon those connected with it. (1877 Annual Report of the Secretery of the Navy, pg. 119).

In November 1877, Commander George P. Ryan, captain of USS Huron, received the following orders to continue the crew’s work in mapping navigational hazards.

SIR: On the 15th November proximo, or as soon after as the Huron, under your command, is ready for sea, you will proceed to Havana, island of Cuba, whence carrying your longitude from the determined position of the Mora, 82° 21' 30" west, you will make a reconnaissance of the coast of Cuba, determining the doubtful points in positions, in coast-lines and in outlying dangers, in accordance with the summary showing the discrepancies on standard charts, &c., with references and notes for your guidance, furnished by the Hydrographic Office to the Bureau of Navigation by direction of this department, and already forwarded you by express.

The vessel under your command is still attached to the North Atlantic station and performing this special service in connection with those of a cruiser. You will therefore keep the commander-in-chief fully advised, and in advance, of your movements, as far as possible, as well as this department and the Bureau of Navigation of the progress of the scientific work in which you are engaged.

Very respectfully,

R. W. THOMPSON,

Secretary of the Navy.

Commander G. P. RYAN,

Commanding United States Steamer Huron,

Navy-Yard, New York.

On November 23rd, despite warnings of an approaching southeasterly gale, USS Huron left Hampton Roads and put to sea.

USS Huron as illustrated in the December 14th, 1877 issue of Harper’s Weekly.

The Wreck of USS Huron, November 24th, 1877

November 23rd, 1877 USS Huron was steaming south along the North Carolina coast. Despite the storm warnings, Commander Ryan expected nothing more than a moderate gale. Ryan set Huron on a course inshore of the Gulf Stream in order to make the fastest possible passage to Port Royal, South Carolina.

The weather deteriorated and the wind and seas rose through the evening of the 23rd. Around 6pm the jib stay carried away. A storm fore staysail was substituted, and reefs put in the fore and main trysails while the spanker was taken in. The ship was making about five and a half knots under steam and reduced sail as the wind blew harder from the east south east. The ships’ officers felt confident that they were far enough off the lee shore to their west.

Just after 1am, on the morning of the 24th, USS Huron ran hard aground.

Master William P. Conway, the senior surviving officer of Huron testified at the inquiry to her loss,

“I was awoke by a heavy shock. Thought at first it was a collision with another vessel, as I heard the water rushing over the rail. At the next thump I knew the ship was ashore, and heard some one say so, and heard some one on deck sing out, "Hard a-starboard." I went on deck as quickly as possible. Found the ship on her port bilge, inclining about 40°.”

USS Huron attempting to head against the gale the night of November 23rd - as illustrated in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper - December 8th, 1877.

Soon, the sea was breaking over the ship, and the boats on the port side were carried away. The Executive Officer, Lieutenant Sydney Simons, ordered the guns be cast overboard, though that proved impossible. Rigging was cut away and masts fell.

The engineers below decks tried to keep the engine backing to pull the ship off, but water poured into the ship from hatches on deck. They tried to keep the fires in the boilers going, but with the ship pounding against the bottom the starboard boiler eventually started breaking loose. At forty pounds steam pressure, the engine suddenly stopped and the remaining steam went screaming out of the whistle. (Statement of Assistant Engineer Denig, Army Navy Journal.)

John Morris Endicott (USNA Class of 1883) would write, “The situation was then appalling and desperate, the ship in total darkness except for a few hand lanterns, enormous waves rolling over her port bulwarks and deluging the wreck-strewn waist, and the wrecked masts hanging by their rigging and pounding about.”

Ensign Lucian Young, who had been asleep in his cabin when the ship struck, reported, “The captain then ordered me to burn all the signals I could. In the meantime all the port boats and cutter had been carried away. The ship was lying on her port side, bilged; her broadside inclined about forty degrees, and the seas breaking clear over her. I next went into the cabin and saved two boxes of Costar lights, and sent up five rockets besides burning over one hundred signals. The sea was then caving in the cabin rapidly. "When I heard the order for "all hands to go forward as quick as possible,' I hurried the quartermasters who were with me and some other men to go forward. As I passed the cabin door Mr. French asked me if that was all I stopped and told him "Yes." Then he said, "We must be quick.' We all started forward together. I had held on to the Gatling gun, when a very heavy sea came over and washed me and about five others down to leeward. All but myself went under the sail and were drowned. I was caught in the bag of the sail and had both legs hurt by being thrown against the gaff. I then regained the gear of the nine-inch gun, and worked myself forward, though I saw Mr. French go in the main rigging. Also saw a number of the men standing in starboard gangway and in the first launch and another lot of men underneath the topgallant forecastle. I succeeded in getting upon the topgallant forecastle, with the assistance of those men already there. A number of men had on life-preservers and one rubber balsa was rigged on the forecastle. Two or three of the men lashed themselves to the bowsprit. Everyone was perfectly cool and showed no signs of fear. The majority of us got close together on the upper side of the forecastle, suffering much from cold and exposure. The seas would break clear over us and nearly suffocate us.” (Report printed in the Army Navy Journal of December 1st, 1877)

The Wreck of USS Huron - Naval History and Heritage Command: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nhhc-series/nh-series/NH-53000/NH-53410.html

The dwindling number of survivors aboard the stricken Huron spent hours huddling on the forecastle and the bowsprit. They looked toward land hoping to see signs of rescue - still not sure how far from the beach they were.

With no rescue in sight, Ensign Young and Seaman Antonio Williams succeeded in freeing a balsa raft from the wreckage of the rigging. They attempted to use the raft to take a line from the ship to the shore, but they reached the end of their rope and had to cut their raft free. Though they feared that they were being swept out to sea, the surf carried them, quite roughly, to the beach. Young and Williams landed three quarters of a mile north of the wreck. Heading back down the beach towards the wreck, they found “ten or fifteen” civilians standing on the shore looking out at the wreck. These men had seen the rockets and signals which Young had fired. When Young asked where the nearest life-saving stations were, he was told that one was four miles away and the other seven. He asked why neither station had responded and was told that the crew of one was way on Roanoke Island, and the other was unmanned. Young then asked why no one had gone to get the lifeboat from the unmanned station and was told by the men that they were afraid to break into the station building.

Young recruited volunteers from the civilians to go to the life saving station where he broke open the building and took the mortar and line back towards the wreck. However, by this time it was daylight, and no one could be seen on the wreck - which was a mere 250 yards from the beach.

A surviving crew member who was washed overboard but successfully made it ashore reflected that, “I think a good many could have saved themselves, but they remained aboard so long in expectation of getting assistance from shore that their limbs became benumbed and useless.” (See: The Army and Navy Journal. Vol. 15. December 1st, 1877. Pages 261-263.)

Ninety eight of USS Huron’s crew, including her Captain, Commander Ryan, and Executive Officer, Lieutenant Simons, would perish in the shipwreck. Only thirty four staggered ashore on the beach at Nags Head. All waited for a rescue which never came.

Master W.P. Conway, the senior surviving officer, concluded his first report following the disaster with the pointed words, “If the life saving station had been in operation and we could have gotten a line from here, all hands might have been saved.” (Army Navy Journal, Page 261).

In this Thomas Nast cartoon, Uncle Sam remarks, “I suppose I must spend a little on life-saving service, life-boat stations, life-boats, surf-boats, etc.; but it is too bad to be obliged to waste so much money". Harper’s Weekly. December 29th, 1877. via Wikimedia.

The Wreck of USS Huron would be followed by that of Steamship Metropolis which on January 31st, 1878 went aground near Currituck nearly midway between two lifesaving stations which were ten miles apart. The wrecked passenger ship was not immediately noticed, and the response of the lifesaving station that did respond was slow, inadequate, and just unlucky. Eighty-five passengers and crew of Metropolis lost their lives.

The two tragedies galvanized public opinion which spurred Congress to act. After a proposal to transfer control of the Life-Saving Service to the Navy was defeated, a bill which established the United States Life-Saving Service as a separate agency within the Department of the Treasury, authorized the construction and manning of over thirty additional life-saving and lifeboat stations, including fifteen on the Virginia-North Carolina coast, and provided that stations would be manned from September 1st to May 1st was passed by Congress and signed by President Hayes on June 18th, 1878.

The crews of the US Life Saving Service would save tens of thousands of mariners and their passengers in distress over the coming decades. In 1915, the Life Saving Service merged with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the United States Coast Guard. (See Means, Dennis R. “A Heavy Sea Running: The Formation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1846–1878.”)

A Lyle Gun and its line wrapped around the spindles on the cart are seen in this circa 1908 Photo. Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016795935/

The Life-Saving Lyle Gun

Prompted by disasters such as these, in the fall of 1878, Lt. David A. Lyle, US Army Ordnance Corps, completed work on a new line-throwing life-saving gun. They were lighter than the small mortars and other artillery pieces previously used - an incredibly important factor when they had to be dragged over sand, but they were also far more effective than older guns which had not been designed for the purpose. The line thrown would be used to carry a heavier cable between the beach and a stranded vessel, and the heavier cable used to deliver people to safety.

The Lyle Gun weighed just 202 pounds and could throw a line 695 yards out. The little cannons designed to save lives would become a standard piece of equipment at the stations.

Lyle Gun - North Carolina Maritime Museum in Southport, North Carolina

Older Lyle Gun marked “US, LSS” on it’s trunnion at Old Baldy, Bald Head Island, North Carolina

North Carolina Historical Marker near the site of the Wreck of USS Huron. Photo Courtesy of the Facebook Page: USS Huron Shipwreck.

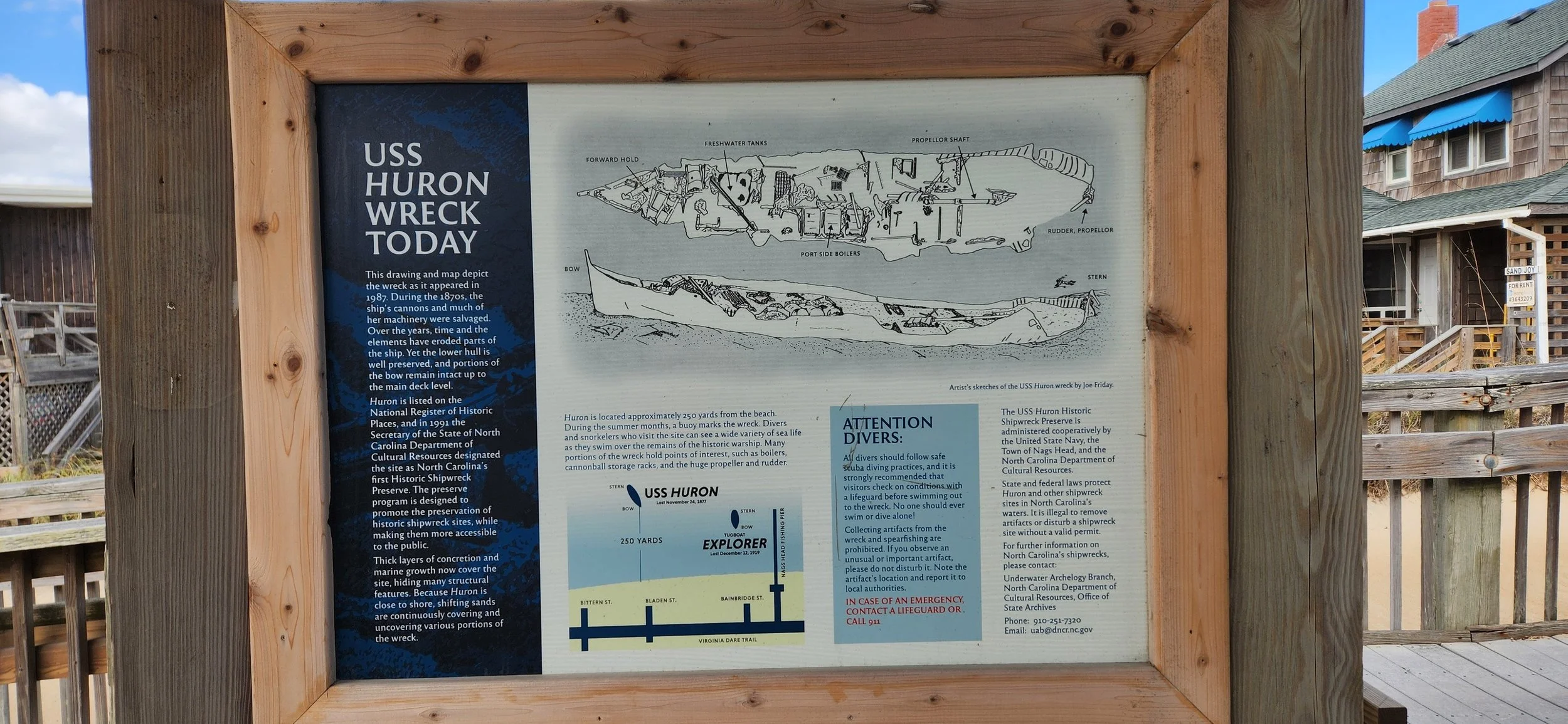

The Wreck Today

The wreck site of USS Huron was designated in 1991 as North Carolina's first Historic Shipwreck Preserve. To learn more about the wreck and see current photos, please follow the Facebook Page, USS Huron Shipwreck. The town of Nags Head has a great video on the wreck site with information about diving on it. That video may be seen on YouTube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4INSZvwPxE

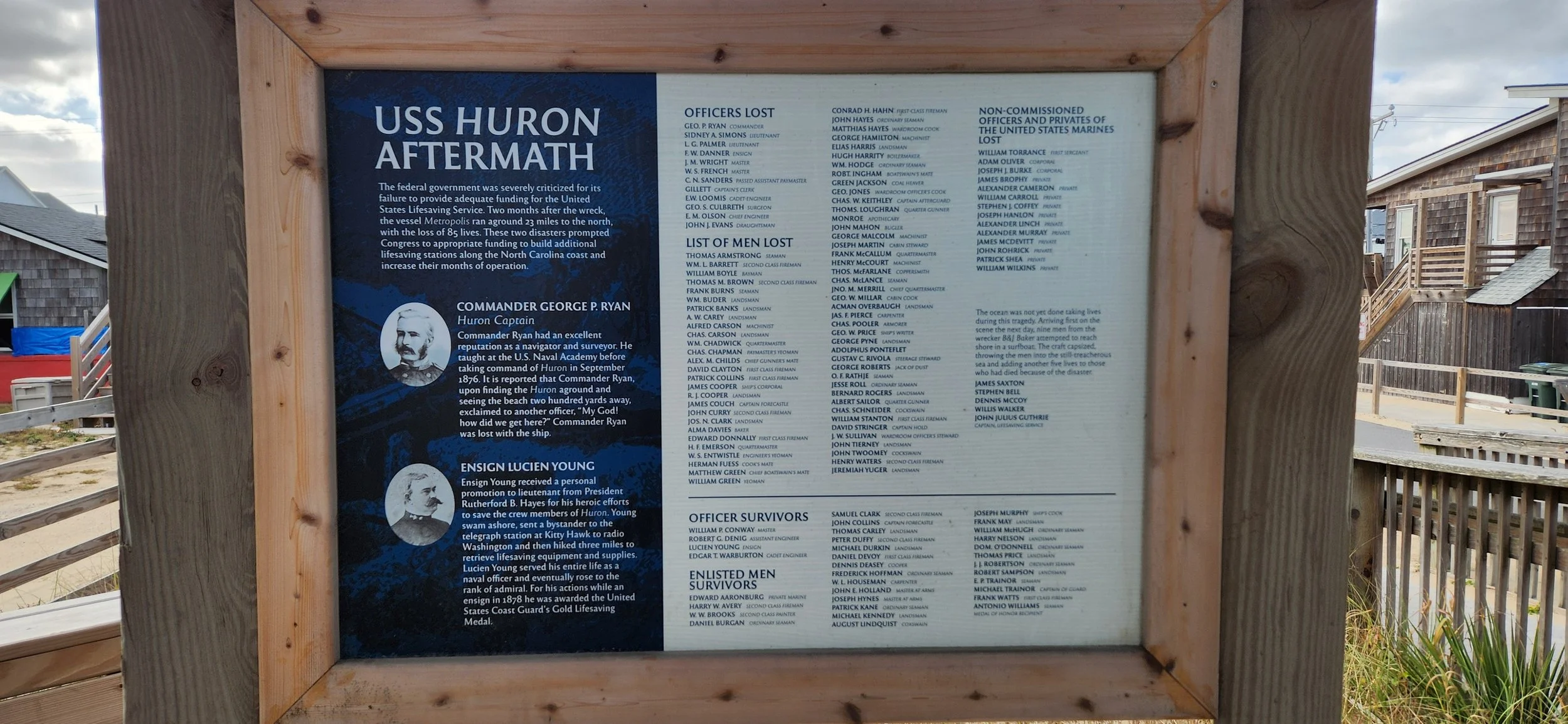

An outdoor history museum gazebo is located at the public beach access on Nags Head closest to the wreck. Photos of the museum courtesy of USS Huron Shipwreck.

What Caused the Wreck of the Huron?

In 1877 USS Huron was a new, iron-hulled ship with good engines. Her two sister ships would see long service lives. USS Alert, seeing long years of service as a cruiser, then training ship, then submarine tender wouldn’t decommission until 1922. USS Ranger, eventually renamed USS Nantucket and eventually T/S Emory Rice, would serve in training roles for the Navy, Massachusetts, and the Merchant Marine Academy until 1944. She would have a short life as a museum before being scrapped in 1958 - the last floating survivor of the 1870s US Navy.

Had Huron not wrecked, she may have seen a similar long life. What was the cause of the disaster that claimed the life of ninety-eight men?

The US Navy Court of Inquiry judged that Commander Ryan was primarily responsible for the wreck, finding, “It is the opinion of the court that with due caution and by carefully taken and plotted bearings of Currituck light, the close proximity of the Huron to the coast would have been made manifest; and, further-more, that it was unseamanlike to carry sail on a lee-shore, those sails lifting, and the natural desire to keep the sails full probably inducing the quartermaster to run to leeward of his course, and the lifting sails having a tendency to drag the vessel to leeward.”

Retired US Navy Captain John Morris Ellicott (USNA Class of 1883) would write in a 1941 Proceedings article, “a cautious captain, when the wind got beyond a moderate gale, would have put the ship on the starboard tack and stood offshore until it abated. But Commander Ryan was fearless, self-confident, and tenacious. When bearings of Currituck Light House showed that the ship had maintained her prescribed course up to 6:00 p.m., he felt confident that in spite of the onshore gale she was going to hold her course throughout the night. In fact he still believed she was on it when she grounded, and had struck an uncharted offshore knoll.”

Elliott also placed blame on the Officer of the Deck who, after Commander Ryan went below, did not call his captain back on deck as the weather worsened, and Elliot speculated that the heal of the ship under canvas caused the magnetic compass, the deviations of which were not perfectly understood in an iron hull, to change slightly in its bearing. (See: Ellicott, John Morris. “October, All Over.”)

After concluding it’s work on Saturday, December 15th, 1877, the Court of Inquiry would meet again on Monday, December to make a few small corrections to their report and adopt one additional sentence:

"In conclusion, the court would state that the evidence shows that many well-found merchant-steamers, wooden and iron, commanded by experienced navigators of our coast, have been wrecked near the point on which the Huron was lost."

The Outer Banks of North Carolina would continue to be known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic”, but thanks to the improvements to the US Life Saving Service introduced in response to the loss of Huron, fewer sailors and the passengers who they ferried would lose their lives upon that treacherous shore.

US Navy 9-Inch Dahlgren Number 1178

US Navy 9-Inch Dahlgren Number 1178 on an original iron carriage at Trophy Park at Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, Virginia

Works Consulted:

The Army and Navy Journal and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces. Vol. 15. Issue of December 1st, 1877. Pages 261-263. Accessed via: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924069759979&seq=273

Transcript of the Court of Inquiry into the Loss of USS Huron. Accessed via: https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~familyinformation/history/transcripts/huron.html

Canney, Donald L. The Old Steam Navy: Frigates, Sloops, and Gunboats, 1815 - 1885. Naval Institute Press, 1990.

Ellicott, John Morris. “October, All Over.” Proceedings. Vol. 67/12/466. December, 1941. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1941/december/october-all-over

Means, Dennis R. “A Heavy Sea Running: The Formation of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, 1846–1878.” https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1987/winter/us-life-saving-service-1.html

Holloway, Anna Gibson. “USS Huron: From National Tragedy to National Register.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BD2qIoPong&t